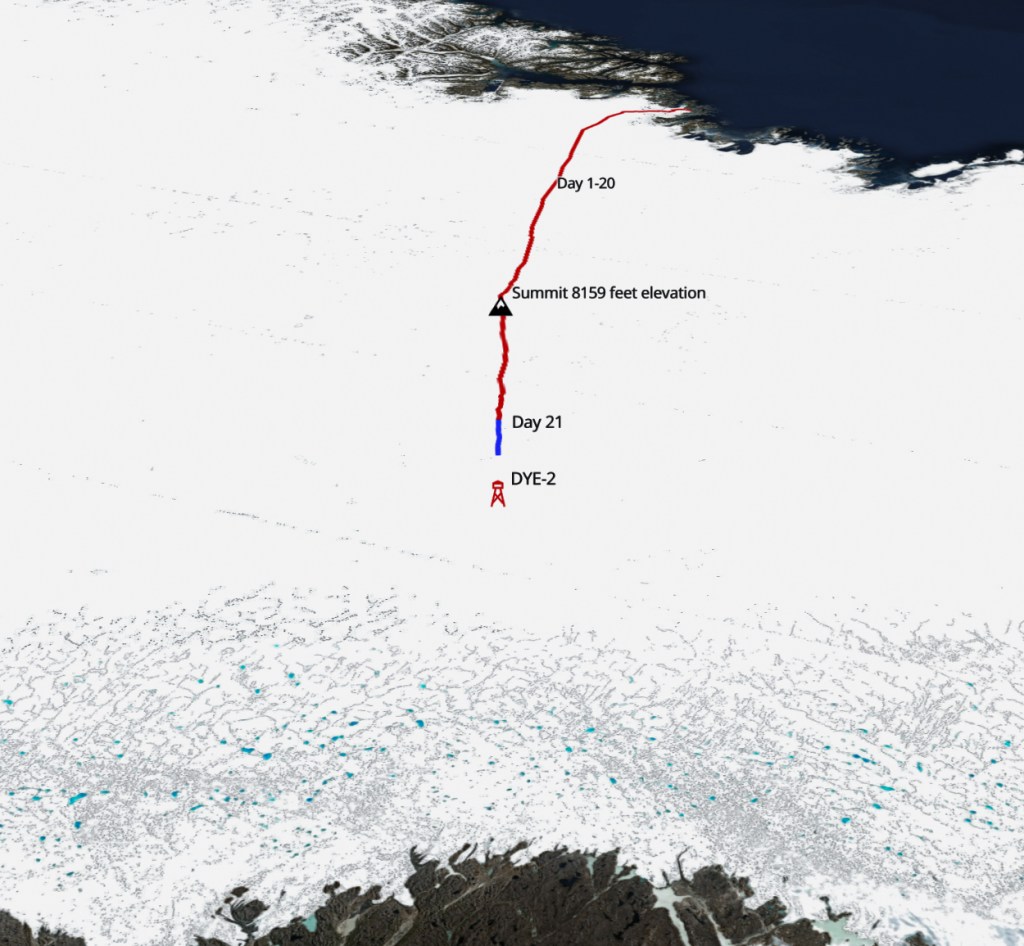

September 4 – 21 km, camped at 7,169 feet

It rained through the morning.

Not the dramatic sideways storms of previous days. Just steady soaking rain. The kind nobody loves skiing in, especially twenty-one days into a Greenland Ice Sheet crossing. We slept in, listening to it drum against the tent, pretending patience was a strategy rather than simple reluctance.

While melting snow for water, I made a mistake. The fuel ran out mid-burn and I tried to disconnect the canister while it was still attached to the fuel line. Trickles of fuel spilled onto the hot stove and flashed instantly. Flames rolled across the cooking platform.

Instinct took over. I buried the stove in snow and kicked it outside the tent. The pump was destroyed. Soot sprayed across the vestibule. The whole thing was over quickly, but the adrenaline stayed. We were lucky. Really lucky. We had a backup pump, but out here redundancy is not comfort. It is survival.

Elaine later pointed out that in the process of throwing the stove outside, we accidentally burned a perfect outline of a snowshoe hare into the snow. Black soot against white crust. The kind of absurd, slightly unhinged humor that only appears when everyone is tired and damp and still functioning.

Lesson filed permanently. Never disconnect fuel from a still hot stove.

We did not start skiing until 1 p.m., but the afternoon turned into a solid push. Twenty-one kilometers, steady and quiet. The rain eased. Snowfall faded. Wind stayed low. The sun flickered through broken cloud layers, dancing along the western horizon in pale gold bands that never quite became sunset but suggested it anyway.

Travel was strange. The front of the line plowed through soft clumping snow. Slow, heavy work. The track behind glazed over quickly, turning into a slick runway for those following. It created two completely different experiences, depending on where you stood in the rotation.

Eirik laid down a strong, fast opening shift. Some in the group were frustrated by the pace, but I quietly enjoyed it. If anything, I felt a small sense of solidarity with him. My own pace had drawn criticism at times earlier in the trip. Moving quickly feels natural to both of us, and it can be a delicate balance between efficiency and group rhythm.

Elaine and I still ended up leading two shifts. By this point we had been spending hours at the front nearly every day. Navigation, pacing, trail breaking. It is simply where we found ourselves most useful. Out here, everyone carries weight for the group in different ways. Some of it is visible. Some of it is not.

With so little sensory variation on the icecap, memory becomes its own terrain. I found myself drifting back to middle school in North Dakota. The smell of baseball diamonds in late summer. Camping trips in Theodore Roosevelt National Park. The endless horizons of Montana. It felt strange and perfectly natural at the same time. The brain reaching for texture when the world around you is reduced to white, gray, and wind.

By evening snow conditions deteriorated into sticky clumping snow that grabbed at skis and pulks. We called camp efficiently, slipping into the practiced choreography that had developed over three weeks. Water melted. Gear dried. Chores finished quickly.

Then the sky exploded.

The aurora arrived without subtlety. Green ribbons unfurling across the sky, twisting and pulsing overhead. We stood outside for nearly an hour, forgetting cold and fatigue entirely. Caroline, Arjen, Elaine, and I worked cameras. Carol launched a drone into the glowing sky.

The lights moved like weather. Like ocean swell. Like something alive and impossibly distant at the same time. Moments like that recalibrate everything.

The Greenland Ice Sheet stopped feeling like an obstacle and started feeling like a place. Vast, austere, and quietly beautiful. I found myself appreciating it in a way I had not earlier in the crossing. The suffering fades faster than the awe.

The descent westward had finally begun to steepen slightly. For days the drop had been almost imperceptible. Now it felt real, even if subtle. DYE-2, the abandoned Cold War radar station buried deep in the ice, sat somewhere ahead of us, likely reachable tomorrow night. A strange landmark to aim for. A relic of global tension, now serving as a waypoint for tired skiers pulling sleds across the ice sheet.

Greenland has a way of layering time like that.

For now we crawled into sleeping bags under a sky still flickering green, knowing we were getting closer to the western edge of the ice and whatever waited between us and the coast.

Leave a comment